I often tell people, that as an Atheist, I believe in energy, but not in spirituality. It means that I stay mindful of what is rather than what isn’t. That I am invested in the earth rather than in the imaginary.

People often describe the intense feeling of being interconnected with all of life as a spiritual experience. I see that experience as simply tapping into what we actually are—elements of earth that are all part of the life source that it grows in cycles of time. When my niece stayed with me last summer, she observed how I interact with other life forms. Whether it was being mindful of tiny crabs under rocks at the beach, or the way that I show respect and appreciation for my two cats, she was intrigued by how I strive to honor all of life. If we’re only aiming to think of ourselves in the scheme of our environment, then we fail the environment completely, of which we are a part. For me, this is a meditative state of living within an awareness of all energy and life forms. That’s not to say I’m always in that state, but I aim for it. In all honesty, it is most difficult to feel that way towards other humans when they can be challenging to deal with.

In comparison to the state of being grounded in nature, spirituality specializes in the things that are unseen and unverified. It generally believes in the existence of “souls,” but only for human beings. Spirituality either makes gods of imaginary entities, or of the universe itself. Because its basis is within the imagination, it breeds superstitions of all kinds that build fear in people, and lead to an obsessive development of rules and regulations. In both the East and the West (except in extremely ancient and indigenous traditions), it furthers the concept that we must transcend the body through prayer and rituals of purification, that lead us toward the dream of immortality after death, or reincarnation.

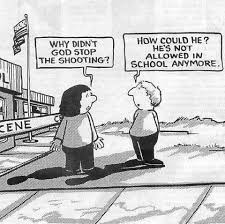

I’ve been working on my book, on the history of religion and conquest, for the past three years now. It’s been a fascinating journey, and what continues to be most striking is the interconnection of myth stories throughout time and region. It is also interesting to perceive exactly when certain ideas took shape, and how they affected culture on a massive scale. For example, if a person comes to a vague idea about what it takes to get to paradise (and imaginary ideas are always vague), they may do whatever it takes to get there, even if that means killing hundreds of people for the glory of their god. If they believe that the apocalypse will occur in their own lifetime, they may live in extremes of piety, seeking signs and symbols at every turn. And if they believe in purity, they will attempt to regulate bodies and control women through a rigid patriarchy. These various reactions then become layered in the culture, both within these beliefs, and outside of them.

Every decade, the number of people who attend church in the U.S. goes down. According to the Public Religion Research Institute, in 1986 only 10 percent of young people (eighteen to twenty-nine) claimed to be religious “nones,” while in 2016 that category went up to 39 percent.[1] One aspect of that shift, is that our sense of ethics has grown beyond religious literature and institutions. In my own case, when I read the Bible I’m struck by the violence, the hatred for outsiders, and the way in which women are property with less rights than they ever had before. In the New Testament, the Evangelical concept of “family values” appears ironic next to the words of Jesus telling his followers to leave their families and follow him. Adding to this ethical disconnect, in the age of science, people are less susceptible to a literal belief of myth stories.

Two attacks that I often see made against Atheists is that we must either be nihilists or pantheists. Even in my dashboard dictionary, the example for nihilist is: “dogmatic atheists and nihilists could never defend the value of human life.” My question is, why does life lose value without a belief in things that don’t exist? Shouldn’t life have more value if I only believe in existence? As for the view that I must be a pantheist, this assumes that as a human, I must worship something. I don’t believe in worshipping anything at all.

Instead, I am simply aiming for awareness. Activities that bring me toward this daily goal are:

- Exercise – to achieve balance in mind and body.

- Expression – for meditation and reflection.

- Experience – to build connection within a diverse community.

- Empathy – through understanding other points of view.

- Exploration – which brings clarity from being outside of routines.

This is my practice of cultivating presence in an energetic world that is alive, and therefore constantly shifting and in flux. These points might sound basic, but I find them challenging because every day is a new beginning. For example, I have days when I would like to avoid flow, and stay within a rigid space of control. It is easy to grow cynical and hard. Much more of a challenge, however, to remain open and flexible and alert to the experience of life.

[1] Fred Edwords, “Faith and Faithlessness by Generation: The Decline and Rise are Real,” The Humanist, August 21, 2018, https://thehumanist.com/magazine/september-october-2018/features/faith-and-faithlessness-by-generation-the-decline-and-rise-are-real.